In 1837, New Jersey and most of America suffered years of massive economic collapse. Most Americans knew it was caused by “systemic corruption” and unsustainable debt in state government. In 1844, New Jersey and most states adopted new state constitutions to fix these problems.

“Systemic corruption” happened when politicians enacted laws that did not apply equally to everyone. They instead were “special” laws that gave special benefits to political friends or punished or ignored opponents. It was difficult for any major business to succeed without getting special laws or financial help from politicians in Trenton. It was therefore normal for the biggest businesses in New Jersey to give massive financial help to politicians who helped them. As the same time, politicians could not win elections without financial support from big businesses. This “systemic corruption” allowed wasteful and inefficient businesses to succeed, while causing good businesses to fail.

New Jersey fixed that problem with provisions in its 1844 State Constitution that required all laws to be uniform throughout the state. This made it difficult or impossible for politicians to make special laws that only applied to help friends or hurt opponents. In 1875, an additional “Tax Uniformity Clause” was added to our State Constitution. It specifically provided that all real estate in New Jersey “shall be assessed according to the same standard of value. . . and taxed at the general tax rate of the taxing district in which the property is situated”.

Another cause of the 1837 economic collapse in America was unsustainable government debt. New Jersey and other state governments borrowed massive amounts of money that could not be paid back without massive tax hikes that ruined many people. When state governments could not collect enough taxes to pay their debts, banks collapsed, and many people lost their life savings.

To fix this problem, the 1844 New Jersey State Constitution added a “Debt Limitation Clause”. This required state government to have balanced budgets every year. It also did not allow the state to borrow money without approval by voters in special referendum votes.

Since the 1960s, the New Jersey Supreme Court refused to apply and enforce these key provisions of our 1844 State Constitutions. They allowed state politicians to use all sorts of excuses to adopt laws that gave all sorts of special deals and benefits for special people–just like in 1837. New Jersey’s Supreme Court also allowed the “Debt Limitation Clause” of our State Constitution to become meaningless. Since the 1960s, the New Jersey Supreme Court has allowed state politicians to set up dozens of “independent authorities” that have borrowed hundreds of billions of dollars. They include the New Jersey Economic Development Authority, the NJ Transportation Trust Fund Authority, and the South Jersey Transportation Authority. They also allowed the state to promise billions of dollars of future pension payments without setting aside enough money to pay for them.

Since the 1960s, our New Jersey Supreme Court has allowed state and local politicians to do the exact same things that caused years of nationwide economic collapse beginning with “The Panic of 1837”.

SETH GROSSMAN

Below is the decision and opinion of the Appellate Division of the New Jersey Superior Court dated October 21, 2024:

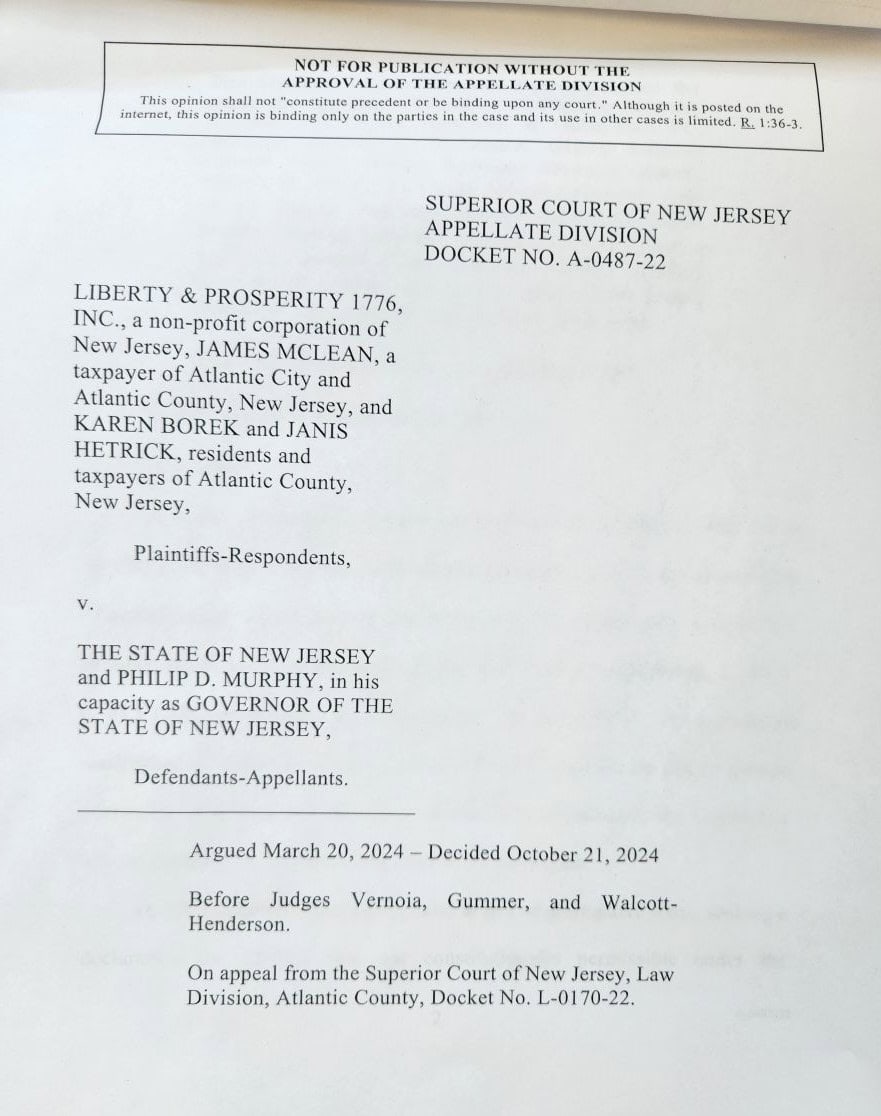

SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY

APPELLATE DIVISION

DOCKET NO. A-0487-22

LIBERTY & PROSPERITY 1776,

INC., a non-profit corporation of

New Jersey, JAMES MCLEAN, a

taxpayer of Atlantic City and

Atlantic County, New Jersey, and

KAREN BOREK and JANIS

HETRICK, residents and

taxpayers of Atlantic County,

New Jersey,

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

v.

THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY

and PHILIP D. MURPHY, in his

capacity as GOVERNOR OF THE

STATE OF NEW JERSEY,

Defendants-Appellants.

______________________________

Argued March 20, 2024 – Decided October 21, 2024

Before Judges Vernoia, Gummer, and Walcott

Henderson.

On appeal from the Superior Court of New Jersey, Law

Division, Atlantic County, Docket No. L-0170-22.

Tim Sheehan, Deputy Attorney General, argued the

cause for appellants (Matthew J. Platkin, Attorney

General, and Chiesa Shahinian & Giantomasi PC,

attorneys; Michael L. Zuckerman, Deputy Solicitor

General, Jean P. Reilly, Assistant Attorney General,

Melissa H. Raksa, Assistant Attorney General, Amy

Chung, Deputy Attorney General, Abiola G. Miles,

Deputy Attorney General, Victoria G. Nilsson, Deputy

Attorney General, Tim Sheehan, Deputy Attorney

General, of counsel and on the briefs; John Lloyd,

Ronald L. Israel, Brian P. O’Neill, on the briefs).

Seth Grossman argued the cause for respondents.

The opinion of the court was delivered by GUMMER, J.A.D.

Plaintiffs – a non-profit corporation, an owner of taxable real estate within

the City of Atlantic City, and residents and owners of taxable real estate within

Atlantic County – challenged the Casino Property Tax Stabilization Act (CPTSA

or Act), N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-18 to -28, and its 2021 amendment, L. 2021,

c. 315 (2021 amendment or Amendment). In the CPTSA, the Legislature

established a “payment in lieu of taxes” (PILOT) program for casino gaming

properties located in Atlantic City. In the 2021 amendment, the Legislature

altered the formula for calculating the PILOT payments.

In 2022, plaintiffs filed a complaint in lieu of prerogative writs, seeking a

declaration the CPTSA was not constitutionally permissible under the

A-0487-22

Page 2

Uniformity Clause set forth in Article VIII, Section 1, Paragraph 1 of the New

Jersey Constitution and the 2021 amendment was null and void.

Defendants moved to dismiss the complaint; plaintiffs cross-moved for summary-judgment.

The motion court granted in part and denied in part each motion. The

court found the Legislature had passed the CPTSA:

to prevent the insolvency of Atlantic City, to facilitate

the municipality’s rehabilitation and recovery, and to

protect the citizens not only of the City, but of Atlantic

County, the region and the State from the ramifications

of what would have otherwise been the imminent

financial collapse of a tax base which uniquely funds

State programs for senior citizens and disabled adults.

Holding the CPTSA had been “enacted for a public purpose” and had

“indisputably fulfilled that public purpose for the benefit of residents of the City,

the County, and the State,” the court concluded the CPTSA fell within the

Exemption Clause of Article III, Section 1, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution and

dismissed the part of the complaint in which plaintiffs sought a declaration the

CPTSA was unconstitutional. The court nevertheless found the Legislature had

not acted rationally or in furtherance of a public purpose in enacting the 2021

amendment to that Act and, in an August 29, 2022 final judgment, declared the

2021 amendment null, void, and of no effect.

Page 3

Defendants appeal from the portion of the judgment nullifying the

Amendment. They argue plaintiffs did not overcome the strong presumption of

validity vested in the Amendment. They contend the Amendment, like the Act

whose formula it seeks to adjust, rationally advances public purposes and falls

within the Exemption Clause.

Plaintiffs did not appeal from the portion of the judgment regarding the

constitutionality of the CPTSA. Thus, it is undisputed the CPTSA wasn’t a

subsidy favoring a particular type of business or a tax break for a failing industry

but instead, as the court found, served a public purpose that benefited citizens

of the local community and across the State.

Plaintiffs now seem to accept some, if not most, of the Amendment’s

provisions. Plaintiffs, for example, embrace the Amendment’s two-percent

upward adjustment in the PILOT payments under certain conditions, see

N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(f); they just complain the percentage is “not nearly”

enough. Plaintiffs focus their criticism on one aspect of the Amendment: the

Legislature’s exclusion of “revenue derived from Internet casino gaming and

Internet sports wagering during calendar years 2021 through 2026” from the

definition of “[g]ross gaming revenue.” See N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(a).

Page 4

Defendants, in reply, fault plaintiffs – and the motion court – for viewing

the provisions of the Amendment in isolation, rather than considering them as a

“cohesive whole,” linked to the constitutional Act and part of a decades-long

comprehensive legislative scheme. We agree and, accordingly, reverse the

court’s striking of the Amendment as unconstitutional.

I.

To put the CPTSA and its 2021 amendment in perspective, we provide

some historical background regarding legislative acts and constitutional

amendments concerning Atlantic City and the casino-gaming business.

In November 1976, New Jersey voters approved an amendment to our

State’s Constitution that enabled the Legislature to authorize the establishment

and operation of gambling casinos in Atlantic City. N.J. Const. art. IV, § 7,

¶ 2(D) (the Casino Clause); see also State v. Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts,

Inc., 160 N.J. 505, 510 (1999). The Casino Clause also permitted the Legislature

“to license and tax such operations and equipment used in connection

therewith.” Pursuant to the Casino Clause, any law authorizing the operation or

establishment of gambling casinos had to “provide for the State revenues derived

therefrom to be applied solely for the purpose of providing funding” that would

assist “eligible senior citizens and disabled residents of the State” by reducing

Page 5

their property taxes, rent, and utility charges and by expanding their access to

health and transportation services or benefits. N.J. Const. art. IV, § 7, ¶ 2(D).

By “State revenues,” the Legislature meant “the proceeds of a tax, initially

imposed at the rate of eight percent, on the annual gross winnings of casinos”;

it did not mean “the proceeds of other taxes, such as corporate, sales and

property taxes.” Trump Hotels, 160 N.J. at 529.

In accordance with the Casino Clause, the Legislature in 1977 enacted the

Casino Control Act (the CCA), N.J.S.A. 5:12-1 to -233. In passing the CCA,

the Legislature found legalized casino gambling was “a unique tool of urban

redevelopment for Atlantic City” that would “facilitate the redevelopment of

existing blighted areas” and “attract new investment capital to New Jersey in

general and to Atlantic City in particular.” N.J.S.A. 5:12-1(b)(4). Our

Constitution provides that “[t]he clearance, replanning, development or

redevelopment of blighted areas shall be a public purpose and public use” and

that “improvements made for these purposes and uses, or for any of them, may

be exempted from taxation . . . for a limited period of time . . . .” N.J. Const.

art. VIII, § 3, ¶ 1 (the Blighted Areas Clause). The Legislature also found

Atlantic City’s tourism industry was “a critically important and valuable asset”

Page 6

to the State and that “the economic stability of casino operations [was] in the

public interest.” N.J.S.A. 5:12-1(b)(2), (12).

The CCA imposed an annual tax on “gross revenues” equal to eight

percent of those revenues. N.J.S.A. 5:12-144(a). “Gross revenue” originally

was defined in the CCA as “all sums . . . actually received by a licensee from

gaming operations, less only the total of all sums paid out as winnings to

patrons.” N.J.S.A. 5:12-24 (1977). The proceeds collected from the tax were to

be deposited in the Casino Revenue Fund, N.J.S.A. 5:12-145(a), and used

exclusively for the purposes identified in the Casino Clause benefitting eligible

senior citizens and disabled residents, N.J.S.A. 5:12-145(c).

The CCA also “required all casinos whose annual gross revenue exceeded

their cumulative investments in the State to make annual investments in land

and real property improvements in Atlantic City and other parts of the State,

commencing after five years had elapsed, equal to two percent of gross

revenues.” Trump Hotels, 160 N.J. at 521; see also N.J.S.A. 5:12-144 (b) to (d).

A casino that failed to make the required capital investments had to pay “an

annual investment alternative tax [(IAT)] equal to two percent of gross revenue

and payable to the Casino Revenue Fund.” Id. at 511 (citing N.J.S.A. 5:12

144(e)).

Page 7

Casinos, however, made “little or no such investments . . . during the seven

years after the [CCA] took effect.” Ibid. In 1984, the Legislature “revised the

prospective investment obligations of casinos” and created the Casino

Reinvestment Development Authority (CRDA). Ibid. (citing N.J.S.A. 5:12

153). Again recognizing “the casino gaming industry as a unique tool of urban

redevelopment for the city of Atlantic City,” the Legislature identified several

purposes of the CRDA, including “to directly facilitate the redevelopment of

existing blighted areas,” “to address the pressing social and economic needs of

the residents of the city of Atlantic City and the State of New Jersey by providing

eligible projects in which licensees shall invest,” and “to provide licensees with

an effective method of encouraging new capital investment in Atlantic City,

which investment capital would not otherwise be attracted . . . by normal market

conditions . . . .” N.J.S.A. 5:12-160(a), (b). To enable the CRDA to achieve

those purposes, “the Legislature provided casinos with the option of either

paying an additional annual 2.5 percent [IAT] on gross revenues . . . or of

investing annually 1.25 percent of such gross revenues in CRDA bonds or in

investment projects approved by the CRDA.” Trump Hotels, 160 N.J. at 511

(citing N.J.S.A. 5:12–144.1).

Page 8

Atlantic City subsequently experienced a “long-held near monopoly on

East Coast gaming.” Marina Dist. Dev. Co. v. City of Atl. City, 27 N.J. Tax

469, 476 (Tax 2013), aff’d o.b., 28 N.J. Tax 568 (App. Div. 2015). In 2006,

Atlantic City casinos paid $417,528,000 to the State pursuant to the CCA’s

annual eight-percent tax on “gross revenues.” N.J. Div. of Gaming Enf’t,

Summary of Gaming and Atlantic City Taxes and Fees 2 (May 2022). But in

2007, that number fell to $393,707,000. Ibid.

“[B]eginning in 2007 . . . powerful forces were combining to undermine

the Atlantic City casino-hotel market in ways that threatened lasting adverse

economic consequences.” Marina, 27 N.J. Tax at 475. By 2008, it was “readily

apparent” that Atlantic City’s “near monopoly . . . was rapidly being eroded by

the expansion of casino gaming in nearby States.” Id. at 476. In addition, “[t]he

national economy began to soften in late 2007, primarily due to the subprime

housing crisis,” and by late 2008, “the economy suffered a significant downturn

triggered by the collapse of the mortgage markets” and major investment banks.

Id. at 481. “[T]he Atlantic City gaming industry was showing signs of distress,”

with plans for the construction of new casino-hotels being put on hold and other

casino-hotels filing for bankruptcy. Id. at 483-84. The amount of the proceeds

Page 9

collected pursuant to the CCA’s annual eight-percent gross-revenue tax

continued to fall. N.J. Div. of Gaming Enf’t, at 2.

The owner of the Borgata Casino complex successfully challenged the

property tax assessments set by Atlantic City’s municipal tax assessor for the

2009 and 2010 tax years, claiming they exceeded the true market value of the

property. Marina, 27 N.J. Tax at 475. In a 2013 decision, a Tax Court judge

issued judgments significantly reducing those assessments. Id. at 531-32. We

affirmed that decision in 2015. Marina Dist. Dev. Co. v. City of Atl. City, 28

N.J. Tax 568 (App. Div. 2015). In 2015, 6,355 property tax appeals were filed

in Atlantic City, nearly three times the number of appeals filed in 2008.1

The CPTSA was proposed in response to Atlantic City’s “dire situation”

and “fiscal challenges,” which arose in part from casino closures and the “large

property tax refunds” Atlantic City owed to the casinos that had successfully

appealed their property tax assessments. Sponsor’s Statement to S. 1715 (Feb.

29, 2016). The CPTSA’s purpose was “to provide certainty to the casinos with

respect to their financial obligation to Atlantic City, and to provide certainty to

1 That data was provided in the statement of material facts plaintiffs submitted

in support of their cross-motion for summary judgment and was supported by

information contained in an email from a representative of the Atlantic County

Board of Taxation, which was an attached exhibit to the certification plaintiffs’

counsel submitted in support of plaintiffs’ cross-motion for summary judgment.

Page 10

Atlantic City about the financial obligation of the casinos to Atlantic City,

Atlantic County, and the Atlantic City School District.” Ibid.

Enacting the CPTSA, the Legislature found it “appropriate . . . to address

the extraordinary situation in Atlantic City by devising a program that avoids

costly assessment appeals for both the casino operators and Atlantic City, and

that provides a certain mandatory minimum property-tax related payment by

casino properties that Atlantic City can rely upon each year.” N.J.S.A.

52:27BBBB-19(h) (2016). The Legislature described Atlantic City as having

experienced “an increase in unemployment due to the recent closing of four

casino properties”; “a strain on [its] municipal budget due to property tax

refunds required by successful assessment appeals of casino gaming properties;

and an increased property tax burden on Atlantic City and Atlantic County

residents based on the decreasing value of casino gaming properties.” N.J.S.A.

52:27BBBB-19(c) (2016).

The Legislature declared the Act served a public purpose “because

Atlantic City will be able to depend on a certain level of revenue from casino

gaming properties each year, making the local property tax rate and need for

State aid less volatile,” citing “the interest of the revitalization of Atlantic City

and the continuation of the casino industry and its associated economic benefits

Page 11

to the State,” the “unique recreational experience” casinos provide “to the

residents of New Jersey,” and the “support” casino revenues provide to “many

social programs, such as property tax relief for seniors, medical assistance,

housing for disabled residents, transportation assistance, and other social

services programs for elderly and disabled New Jerseyans.” N.J.S.A.

52:27BBBB-19(l), (m) (2016).

The Legislature also found it was “a primary public purpose” of the

CPTSA “to stabilize the casino industry for the benefit of the casino employee

workforce.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19(n) (2016). The CPTSA would “greatly

enhance the ability of the casino gaming properties to adapt their business

models to the changes in the regional casino gaming market, which will in turn

allow them to remain open for business and to pay their employees good wages

and benefits . . . for many years to come.” Ibid. The Legislature determined the

“ability to depend on a stable [PILOT] obligation” would “in turn help to

stabilize the casino business models . . . , and the [Atlantic City] casino gaming

properties w[ould] be better able to compete with out-of-State casino gaming

properties in the region” and “to preserve, and perhaps grow, the many benefits

that casino gaming has brought to the State, and more particularly, to the

Atlantic City region.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19(m) (2016).

Page 12

The CPTSA would achieve those goals in part by mitigating the impact of

the fluctuations in the annual value of the casino properties, which is “greatly

influenced by the performance of casino gaming properties in other nearby states

and by extreme weather events like Super Storm Sandy.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB

19(g) (2016). The Legislature cited its constitutional authority “to grant

property tax exemptions by general law” and declared that laws applying only

to casinos, or “for economic purposes related to casino gaming,” are

constitutional. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19(i), (j) (2016). It explained that Atlantic

City is “a special class unto itself for economic purposes related to casino

gaming” because it is “the only municipality wherein casino gaming is

authorized.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19(j) (2016). It further explained that

“[c]asino gaming properties represent a unique classification of property that

can be exempted from normal property taxation by general law, in favor of a

certain guaranteed mandatory minimum payment in lieu of property taxes when

it is primarily in the public interest to do so.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19(k)

(2016).

In lieu of paying local property taxes, the CPTSA required the owner of a

casino gaming property to sign a ten-year financial agreement with Atlantic

City, promising to remit to the city that property’s “allocated portion of the

Page 13

annual amount of the” PILOT. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(c)(1) (2016). The

PILOT was to be calculated annually “using a formula implemented by the Local

Finance Board, in consultation with” the Division of Gaming Enforcement,

“using the following criteria”: (1) “[t]he geographic footprint of the real

property, expressed in acres, owned by each casino gaming property”; (2) “[t]he

number of hotel guest rooms in each casino gaming property”; and (3) “[t]he

gross gaming revenue of the casino in each casino gaming property from the

calendar prior year.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(c)(4) (2016).

Instead of relying on “gross revenue” as defined in N.J.S.A. 5:12-24 for

the PILOT, the Legislature in enacting the CPTSA introduced the term “gross

gaming revenue” (GGR). N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(a) (2016). It defined GGR

as “the total amount of revenue raised through casino gaming from all of the

casino gaming properties located in Atlantic City,” as determined by the

Division of Gaming Enforcement. Ibid.

The Legislature did not intend in the CPTSA to make a casino’s PILOT

payments for the years 2017 to 2021 greater than the casino’s total real property

tax obligation for 2015. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(c)(4) (2016). For those first

five years, a casino would receive a credit against its IAT obligation equal to the

amount its total PILOT obligation exceeded its 2015 property tax. Ibid.

Page 14

Whatever the total IAT amount was for any year, the portion not already pledged

for CRDA bonds or other CRDA contractual obligations would be “allocated to

Atlantic City for the purposes of paying debt service on bonds issued” before or

after the enactment of the CPTSA. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-25 (2016).

The CPTSA also required casinos to make “additional payments” to the

State through 2023, in an aggregate fixed amount that would be remitted to

Atlantic City for use in its current-year budget. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-21(c)

(2016).

The additional payments started at $30 million for 2016 and

progressively decreased to $15 million for 2017, $10 million for 2018, and $5

million thereafter. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-21(a) (2016).

In 2018, after the United States Supreme Court found unconstitutional a

federal law that made it unlawful for a state to license or authorize gambling on

competitive sporting events, see Murphy v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 584

U.S. 453, 461, 486 (2018), the Legislature enacted a statute that authorized

sports wagering at casinos and racetracks, L. 2018, c. 33. See also N.J.S.A.

5:12A-10 to -19 (the Sports Wagering Act). The Sports Wagering Act was

preceded by a constitutional amendment about sports betting and a statute about

internet gaming.

Page 15.

In 2011 the Casino Clause was amended to allow the Legislature to

authorize “wagering at casinos or gambling houses in Atlantic City on the results

of any professional, college, or amateur sport or athletic event,” excluding “a

college sport or athletic event that takes place in New Jersey or on a sport or

athletic event in which any New Jersey college team participates regardless of

where the event takes place.” N.J. Const. art. IV, § 7, ¶ 2(D); see also Murphy,

584 U.S. at 462 (noting that in 2011, “New Jersey voters approved an

amendment to the State Constitution making it lawful for the legislature to

authorize sports gambling”).

Internet gaming was authorized by statute in 2013. L. 2013, c. 27; see

also N.J.S.A. 5:12-95.17 to -95.33. Internet gaming was defined as “the placing

of wagers with a casino licensee at a casino located in Atlantic City using a

computer network . . . through which the casino licensee may offer authorized

games to individuals . . . who are physically present in this State.” N.J.S.A.

5:12-28.1. “Internet gaming gross revenue” (IGGR) was defined as “the total of

all sums actually received by a casino licensee from Internet gaming operations,

less only the total of all sums actually paid out as winnings to patrons.” N.J.S.A.

5:12-28.2. The Legislature exempted IGGR from the CCA’s eight-percent tax

on gross revenue and instead applied a fifteen-percent tax on IGGR. N.J.S.A.

Page 16

5:12-95.19. The Legislature made IGGR subject to the IAT, except at double

the rates established for gross revenue in the CCA, N.J.S.A. 5:12-144.1,

meaning casinos had to pay an annual five percent IAT on IGGR or provide

2.5 percent of IGGR towards the alternative investment option, N.J.S.A. 5:12

95.19.

In passing the internet-gaming legislation, the Legislature found that

“stop[ping] the illegal Internet gambling market” and controlling how Atlantic

City casinos “accept wagers placed over the Internet for games conducted in

Atlantic City casinos will assist and enhance the rehabilitation and

redevelopment of existing tourist and convention facilities in Atlantic City

consistent with the original intent of the [CCA] and will further assist in

marketing Atlantic City . . . .” N.J.S.A. 5:12-95.17(i). The Legislature again

recognized the “vital interest” the State and general public have “in the success

of tourism and casino gaming in Atlantic City, . . . which by reason of its

location, natural resources, and historical prominence and reputation as a

noteworthy tourist destination, has been determined . . . to be a unique and

valuable asset that must be preserved, restored, and revitalized.” N.J.S.A. 5:12

95.17(c).

Page 17

Pursuant to the Sports Wagering Act, the Division of Gaming

Enforcement is authorized to issue sports wagering licenses to casinos, N.J.S.A.

5:12A-11(a) (2018), and a casino holding a sports wagering license may operate

a sports pool, ibid., which is defined as “the business of accepting wagers on

any sports event by any system or method of wagering,” N.J.S.A. 5:12A-10

(2018). A casino holding a sport wagering license also “may conduct an online

sports pool or may authorize an internet sports pool operator licensed as a casino

service industry enterprise . . . to operate an online sports pool on its behalf.”

N.J.S.A. 5:12A-11(a) (2018). An online sports pool is defined as “a sports

wagering operation in which wagers on sports events are made through

computers or mobile or interactive devices and accepted at a sports wagering

lounge through an [authorized] online gaming system . . . .” N.J.S.A. 5:12A-10

(2018). A sports wagering lounge is defined as “an area wherein a licensed

sports pool is operated located in a casino hotel or racetrack.” Ibid. A casino

operating a sports wagering lounge can offer online sports wagering through an

internet gaming affiliate, N.J.A.C. 13:69N-1.2(c), which is defined as a licensed

“business entity . . . that owns or operates an Internet gaming system on the

behalf of a licensed casino,” N.J.S.A. 5:12-95.32.

Page 18

Like IGGR, “sums received by the casino from sports wagering or from a

joint sports wagering operation, less only the total of all sums actually paid out

as winnings to patrons” were exempted from the CCA’s tax on gross revenue.

N.J.S.A. 5:12A-16. Instead, the Legislature imposed an 8.5 percent tax on those

sums from on-premises sports wagering and a thirteen-percent tax on those sums

from online sports wagering. Ibid. The Legislature also imposed on all sports

wagering revenue an additional tax of 1.25 percent, to be paid to the CRDA “for

marketing and promotion of the City of Atlantic City.” Ibid.

In the 2018 Sports Wagering Act, the Legislature also added the revenue

from “sports pool operations” to the definition of GGR used in determining a

casino’s PILOT payment. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(a) (2018). Without

distinguishing between on-premises and online sports pools, the Legislature

redefined GGR as “the total amount of revenue raised through casino gaming,

including revenue from sports pool operations, from all of the casino gaming

properties located in Atlantic City.” Ibid.

In 2021, the Legislature amended the CPTSA, effective December 21,

2021. L. 2021, c. 315. In amending the CPTSA, the Legislature again

acknowledged it had enacted the CPTSA “to address a dire financial

circumstance that affected casino gaming properties in Atlantic City, and the

Page 19

finances of the city itself.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19.1(a). The Legislature

found the CPTSA had had a “stabilizing effect . . . on the finances of . . . Atlantic

City and the casino gaming industry during the first five years of the law.”

N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19.1(c). According to the Legislature, “Atlantic City’s

overall financial condition [was] more stable since the casino gaming properties

began making PILOT payments” and that “financial stability benefit[ed] the

casinos, their employees, property taxpayers in Atlantic City, and all New Jersey

residents.” Ibid.

The Legislature, however, found that that financial stability might be

“adversely impacted by certain provisions in the [then] current version of the”

CPTSA. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19.1(d). The Legislature specifically referenced

the calculation of the annual PILOT payment, which the Legislature had

designed such that “each casino gaming property would not pay more in the

annual PILOT payments than it paid in property taxes in 2015,” and the

impending 2021 expiration of the IAT credit that a casino received when its

PILOT payment exceeded its 2015 property tax. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19.1(d).

The Legislature also found the public health emergency declared in

response to the COVID-19 pandemic had “negatively impacted tourism in

Atlantic City by restricting the public’s right to travel”; totally and then partially

Page 20

closing casino gaming properties; “and closing other businesses that would have

been visited by tourists to the city for months as well.” N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB

19.1(e). The Legislature was concerned the impact of those

public health emergency limitations on Atlantic City’s

casino gaming properties w[ould] affect the finances of

those casinos for the foreseeable future, and thereby

impact their ability to pay the required PILOT

payments to the city and . . . contribute to the quality of

life of the State’s senior and disabled residents who rely

on casino revenue deposited into the Casino Revenue

Fund to fund programs that reduce property taxes as

well as utility assistance programs benefiting those

residents.

[Ibid.]

The Legislature declared it was a “compelling public purpose for the State

to establish appropriate alternative obligations for the final five years of the”

CPTSA by amending it to (1) “adjust policies to reflect the operations of existing

casino gaming properties and to compensate for the impacts that the [COVID

19 pandemic] public health emergency . . . had and will continue to have on in

person and internet gaming”; (2) “lessen the financial impact of the end of the

IAT crediting mechanism at the end of 2021 on the casino gaming properties”;

and (3) “ensure that Atlantic City continues to receive sufficient PILOT

payments and IAT payments to fund its municipal budget.” N.J.S.A.

52:27BBBB-19.1(f). The Legislature further declared the amendments to be

Page 21

in the best interest of the casino gaming industry which

serves as a vital part of the economy of the State, in the

best interests of Atlantic City, and in the best interests

of the State’s senior and disabled residents who rely on

casino revenue . . . to fund programs that reduce

property taxes as well as rentals, telephone, gas,

electric, and utility charges.

[Ibid.]

The Legislature stated that its authority under the Exemption Clause

“empowered” it “to grant property tax exemptions by general law” and that both

its prior enactment of CPTSA and its enactment of the 2021 amendment were

valid exercises of that authority. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-19.1(g).

In the 2021 amendment, the Legislature, among other adjustments,

redefined GGR for 2021 through 2026. While it retained the phrase “including

revenue from sports pool operations” in the definition of GGR, the Legislature

limited the phrase’s application to revenue from on-premises sports pool

operations by expressly excluding the revenue from online sports pool

operations by adding this sentence to the definition: “For the purpose of

determining the amount of the [PILOT] pursuant to this section, gross gaming

revenue shall not include revenue derived from Internet casino gaming and

Internet sports wagering during calendar years 2021 through 2026 as determined

by the” Division of Gaming Enforcement. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-20(a). That

Page 22

additional language also made clear internet casino gaming revenue was now

expressly excluded from GGR. Ibid.

The 2021 amendment also provided for staged reductions from 2022 to

2026 in the credit a casino licensee would receive against its annual IAT

obligation if its PILOT exceeded its 2015 property tax obligation. N.J.S.A.

52:27BBBB-20(c)(5) to (9). The 2021 Amendment modified the allocation of

the annual aggregate IAT amount for 2022 to 2026. The portion not already

pledged for CRDA bonds or other CRDA contractual obligations would still be

allocated for Atlantic City’s debt service. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-25(b). The

remainder, up to a cap of $13.5 million in 2022 that would grow to $31.1 million

in 2026, was to be allocated first to Atlantic City for “general municipal

purposes” other than debt service, until that allocation was 2.5 percent greater

than the allocation for the preceding year; the rest would then be allocated

among the CRDA, the Clean and Safe Fund, and the Infrastructure Fund.

N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-25(b), (c). The Legislature created in the 2021

amendment the Clean and Safe Fund and the Infrastructure Fund for Atlantic

City’s benefit. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB-25(b), -27, -28. The Legislature in the

2021 amendment extended by three years, to 2026, the casino gaming properties’

Page 23

obligation to make additional payments to the State. N.J.S.A. 52:27BBBB

21(a).

II.

“Our standard of review in determining the constitutionality of a statute is

de novo.” State v. Hemenway, 239 N.J. 111, 125 (2019). Engaging in that de

novo review, we follow these guiding principles.

“[S]tatutes are presumed to be constitutional.” In re M.U.’s Application

for a Handgun Purchase Permit, 475 N.J. Super. 148, 190 (App. Div. 2023).

When considering a facial challenge to the constitutionality of a statute, we

“afford every possible presumption in favor of an act of the Legislature.” Mack

Cali Realty Corp. v. State, 466 N.J. Super. 402, 423-24 (App. Div. 2021)

(quoting Town of Secaucus v. Hudson Cnty. Bd. of Tax’n, 133 N.J. 482, 492

(1993)), aff’d o.b., 250 N.J. 550 (2022). “Reviewing courts are ‘not limited to

the stated purpose of the legislation and “should seek any conceivable rational

basis”‘ to uphold it.” Id. at 424 (quoting Strategic Env’t Partners, LLC v. N.J.

Dep’t of Env’t Prot., 438 N.J. Super. 125, 145 (App. Div. 2014) (quoting

Secaucus, 133 N.J. at 494-95)). “Simply put, ‘the courts do not act as a super

legislature.'” Ibid. (quoting Newark Superior Officers Ass’n v. City of Newark,

98 N.J. 212, 222 (1985)). “Only a statute ‘clearly repugnant to the constitution’

Page 24

will be declared void.” Ibid. (quoting Secaucus, 133 N.J. at 492-93). We have

“recognize[d] that, ‘in the field of taxation, the Court has accorded great

deference to legislative judgments.'” Id. at 424-25 (quoting Secaucus, 133 N.J.

at 493).

“[T]he burden is on the party challenging the constitutionality of the

statute to demonstrate clearly that it violates a constitutional provision.” Ibid.

(alteration in original) (quoting Newark Superior Officers, 98 N.J. at 222).

“That burden is onerous.” Ibid. “A presumption of validity attaches to every

statute” and “‘any act of the Legislature will not be ruled void unless its

repugnancy to the Constitution is clear beyond a reasonable doubt.'” State v.

Lenihan, 219 N.J. 251, 266 (2014) (quoting State v. Muhammad, 145 N.J. 23,

41 (1996)). “Even where a statute’s constitutionality is ‘fairly debatable, courts

will uphold’ the law.” Ibid. (quoting Newark Superior Officers, 98 N.J. at 227).

In finding the Amendment unconstitutional, the motion court did not apply

that standard. The court did not consider the decades of legislative and judicial

findings recognizing the symbiotic and deep-rooted connection between

Atlantic City, the casino industry, and the State as a whole. It did not consider

its own conclusion that the Act was constitutionally permissible under the

Uniformity and Exemption Clauses set forth in Article VIII, Section 1, of our

Page 25

Constitution because it fell within a “public purpose” exemption. It did not treat

the Amendment as an adjustment to the PILOT-payment formula set forth in

that constitutional Act or recognize the Legislature’s determination that an

adjustment to the formula was appropriate to maintain the gains in the financial

stability of Atlantic City obtained as a result of the Act. Rather than reading the

Amendment in conjunction with the Act, the court analyzed the Amendment in

isolation, untethered to the constitutional Act it was intended to amend, as if the

public purpose served by the Act was wholly separate and apart from the

Amendment. It wasn’t.

Instead of “seek[ing] any conceivable rational basis” to uphold the

Amendment, Secaucus, 133 N.J. at 495, the motion court rejected the

Legislature’s rational bases supporting its enactment. The court acknowledged

courts must presume the Legislature’s judgment was based on factual support

when presented with no evidence establishing otherwise. See Reingold v.

Harper, 6 N.J. 182, 196 (1951) (finding “Factual support for the legislative

judgment is to be presumed. Barring a showing contra, the assumption is that

the measure rests upon some rational basis within the knowledge and experience

of the Legislature”); see also N.J. Shore Builders Ass’n v. Twp. of Jackson, 199

N.J. 38, 55 (2009) (same). The court nevertheless rejected the Legislature’s

Page 26

stated conclusions and concerns that led to its enactment of the Amendment

based on its determination that “facts on the record contradict[ed]” those

conclusions and concerns. The court erred in doing so, especially because the

record had not established that the “facts” on which the court had relied were

actually available to the Legislature when it enacted the Amendment.2 A court

cannot render void a legislative act based on information it assumed the

Legislature had or the twenty-twenty prism of future data amassed and presented

after the enactment of a statute.

Given the concerns identified by the Legislature, it was not irrational for

the Legislature to determine the CPTSA’s formula for calculating PILOT

payments should be amended. Reasonable minds might differ as to how the

2The court relied on a Division of Gaming Enforcement report entitled “Atlantic

City Gaming Industry Summary of Gaming and Atlantic City Taxes and Fees,”

and monthly casino revenue reports submitted by casinos to the Division for the

months of November and December 2021. The Division’s report was dated May

23, 2022, more than five months after the enactment of the amendment. The

casino revenue reports for December 2021 were submitted in January 2022, after

the amendment’s enactment. See Division of Gaming Enforcement, Monthly

Gross Revenue Reports, New Jersey Office of Attorney General,

https://www.njoag.gov/about/divisions-and-offices/division-of-gaming

enforcement-home/financial-and-statistical-information/monthly-gross

revenue-reports (last visited Oct. 14, 2024). And although the monthly reports

for November 2021 were submitted to the Division on various dates in

December 2021, it is not clear when the Division made those reports available

on-line.

Page 27

formula should have been amended but in such cases courts must defer to the

Legislature’s judgment.

[O]ur Supreme Court has emphasized “the long

established principle of deference to the will of the

lawmakers whenever reasonable men might differ as to

whether the means devised to meet the public need

conform to the Constitution . . . [and] the equally

settled doctrine that the means are presumptively valid,

and that reasonably conflicting doubts should be

resolved in favor of validity.”

[Mack-Cali, 466 N.J. Super. at 429-30 (quoting City of

Jersey City v. Farmer, 329 N.J. Super. 27, 46 (2000)).]

As we held in Mack-Cali, “[i]t is not for us to dispute the wisdom of the

Legislature’s choice.” Id. at 430.

The motion court found it was “unclear whether the Legislature acted with

. . . noble intentions in passing the Amendment.” But that isn’t the standard a

court applies when considering the constitutionality of a legislative act. A court

cannot rule a legislative act void “unless its repugnancy to the Constitution is

clear beyond a reasonable doubt.” Lenihan, 219 N.J. at 266 (quoting Brown v.

City of Newark, 113 N.J. 565, 572 (1989)). When “a statute’s constitutionality

is ‘fairly debatable, courts will uphold’ the law.” Ibid. (quoting Newark Superior

Officers, 98 N.J. at 227). The motion court did not apply that high standard, and

plaintiffs failed to meet it.

Page 28

For these reasons, we reverse the portions of the August 29, 2022 final

judgment denying in part defendants’ motion to dismiss the complaint, granting

in part plaintiffs’ summary-judgment motion, and declaring the 2021 amendment

null, void, and of no effect. We otherwise affirm.

Affirmed in part; reversed in part.

Page 29

LibertyAndProsperity.com is a tax-exempt, non-political education organization of roughly 200 citizens who mostly live near Atlantic City, New Jersey. We formed this group in 2003. We volunteer our time and money to maintain this website. We do our best to post accurate information. However, we admit we make mistakes from time to time. If you see any mistakes or inaccurate, misleading, outdated, or incomplete information in this or any of our posts, please let us know. We will do our best to correct the problem as soon as possible. Please email us at info@libertyandprosperity.com or telephone (609) 927-7333.

If you agree with this post, please share it now on Facebook or Twitter by clicking the “share” icons above and below each post. Please copy and paste a short paragraph as a “teaser” when you re-post.

Also, because Facebook, YouTube and other social media often falsely claim our posts violate their “community standards”, they greatly restrict, “throttle back” or “shadow ban” our posts. Please help us overcome that by sharing our posts wherever you can, as often as you can. Please copy and paste the URL link above or from the Twitter share button to the “comments” section of your favorite sites like Patch.com or PressofAtlanticCity.com. Please also email it to your friends. Open and use an alternate social media site like Gab.com.

Finally, please subscribe to our weekly email updates. Enter your email address, name, city and state in the spaces near the top of our home page at Homepage – Liberty and Prosperity. Then click the red “subscribe” button. Or email me at sethgrossman@libertyandprosperity.com or address below. Thanks.

Seth Grossman, Executive Director

LibertyAndProsperity.com

info@libertyandprosperity.com

(609) 927-7333