From Prologue: Unprepared and Unprotected. Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates by Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger. Penguin Random House 1915, Pages 1 through 3.

A fast-moving ship approached the American merchant ship Dauphin off the coast of Portugal. However, Captain Richard O’Brien saw no cause for alarm. On this warm July day in 1785, America was at peace. There were many innocent reasons for a friendly ship to come alongside. Perhaps it was a fellow merchant ship needing information or supplies. Perhaps the ship’s captain wanted to warn him of nearby pirates.

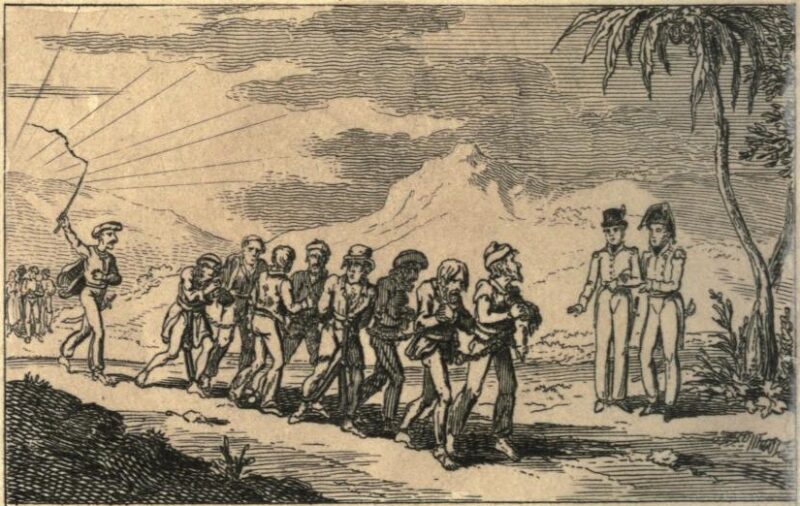

By the time O’Brien realized that the ship did not approach in peace, it was too late. The American ship was no match for the Algerian vessel armed with 14 cannons. A raiding party with daggers gripped between their teeth swarmed over the sides of the Dauphin. The Algerians vastly outnumbered the American crew. They quickly claimed the ship and all its goods in the name of their leader, the Dey of Algiers.

Mercilessly, the attackers stripped O’Brien and his men of shoes, hats, and handkerchiefs, leaving them unprotected from burning sun during the twelve-day voyage back to the North African coast. On arrival in Algiers, the American captives were paraded through the streets as spectators jeered.

The Americans were issued rough sets of native clothing and two blankets each that were to last for their entire period of captivity, whether it was a few weeks or fifty years. Kept in a slave pen, they slept on a stone floor, gazing into the night sky where the hot starts burned above them like lidless eyes, never blinking. Each night, there was a roll call. Any man who failed to respond promptly would be chained to a column and whipped soundly in the morning.

Together with men of another captured ship, the Maria, O’Brien’s Dauphin crew broke rocks in the mountains while wearing iron chains Saturday through Thursday. On Friday, the Muslim holy day, the Christian slaves dragged massive sleds loaded with rubble and dirt nearly two miles to the harbor to form a jetty. Their workdays began before the sun rose and, for a few blissfully cool hours, they worked in the darkness.

Their diet consisted of stale bread, vinegar from a shared bowl at breakfast and lunch, and, on good days, some ground olives. Water was the one necessity provided with any liberality. As a ship captain, O’Brien was treated somewhat better, but he feared his men would starve to death.

“Our sufferings are beyond our expression or your conception,”, O’Brien wrote to America’s ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson two weeks after his arrival in Algiers. Those sufferings would only get worse. Several of the captives from the Maria and the Dauphin would die in captivity of yellow fever, overwork, and exposure. In some ways, they were the lucky ones. The ways out of prison for the remaining prisoners were few; convert to Islam, attempt to escape, or wait for their country to negotiate their release. A few captives would be ransomed. However, for the most, their thin blankets wore out as year after year passed and freedom remained out of reach. Richard O’Brien would be ten years a slave.

America had not yet elected its first President. However, it already had its first enemy.

Prologue: Unprepared and Unprotected. Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates by Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger. Penguin Random House 1915, Pages 1 through 3.